Complete History of the Sanibel Island Lighthouse

Still standing 98 feet above sea level, Sanibel’s historic Light has an incredible history, one that Pfeifer Realty Group has been instrumental in documenting in films, as well as preserving in photos at the Sanibel Library. Both documentaries Sanibel Before the Causeway, and Postcards and Photos from Sanibel were produced by David E. Carter and fully funded by Pfeifer Realty Group. A more whimsical film produced by the incredibly talented Rusty Farst, Sandbars to Sanibel – Pioneering an Island, featured Mary Ellen Pfeifer as Hazel Reed the postmaster’s daughter whose antics create an island wide crisis. We hope you will enjoy the following historical account of Sanibel Island’s beloved lighthouse.

![]()

The lighthouse board first requested funds in 1856 to construct a much-needed light on Sanibel’s east end. A second request was made after the Civil War. $50,000 in funds were finally approved and in 1884 the Sanibel Lighthouse was built 6 years after the initial request was made to the US Congress.

Prior to Sanibel’s lighthouse construction the nearest lighthouse was the Loggerhead Light in the Dry Tortugas. Once built, it was referred to as the Sanibel Island Light and Point Ybel Light. The use of the word Ybel, pronounced “Ebell”, has its own history. When Juan Ponce De Leon thought “discovered” Sanibel in 1513, he named the island “Santa Isybella” for Queen Isabella. Spanish maps later drawn in 1527 indicated the name as “San Ybel” which was again changed by a British Cartographer to Sanybel. Point Ybel stuck and as pioneers began to homestead on the Island, this East End area became known as “Old Town”. One can only assume it was referred to as “old” because it was settled before Wulfert was settled on Sanibel’s West End.

The Sanibel Island Light was desperately needed to guide sailors through San Carlos Bay to Punta Rassa. This port exported free range herds of cattle that were grazed and driven by “Florida Crackers” from Central Florida to board ships to Cuba. Florida cattlemen we often paid with boxes filled with silver doubloons (the book A Land Remembered is an excellent illustration of this rugged time in Florida’s rich history). They earned the nickname “Crackers” from the sound their whips made as they wrangled the herds. Many native Floridians are decedents of these incredibly rugged cowboys of the swamp and proud of the Cracker name.

Prior to the Sanibel Lighthouse construction, the only lights guiding sailors in the Gulf waters were in the Tortugas near Key West and on Egmont Key, a small island at the mouth of Tampa Bay.

In February 1884 the construction of Sanibel’s Lighthouse foundation began. The iron work for both the Sanibel Light and the nearly identical designed Cape San Blas Lighthouse located in the Florida Panhandle were being produced in Jersey City. In preparation for the delivery, a long T-dock wharf was constructed to receive all the remaining construction materials. Unfortunately, the ship carrying the iron work sank only two miles off the coast of Sanibel. Thanks to the skill of a diver and the crew members of the Lighthouse tenders, the majority of the materials were recovered and in 3 months the Point Ybel Light construction was completed.

At 98 feet above sea level, the Sanibel Light used a 900-pound, Third Order Fresnel lens that was powered by kerosine oil. The light was fixed white with a bright flash occurring every 120 seconds. The central cylinder of the structure housed a 127-step spiral staircase to the light chamber and was 20 feet from the ground. The skeletal metal frame design was intentionally created to withstand hurricanes allowing strong winds and waves to pass through it with little resistance and damage. An external staircase spanned the 20-foot gap to the ground.

On August 20th, 1884 the lighthouse was lit for the first time by keeper Dudley Richardson. At that time, it took two men to operate the light taking 12-hour shifts. Every afternoon a 5 gallon can of kerosine was carried up 127 steps to pump the light and each morning the empty can was retrieved to repeat the process. To keep the light flashing tempo finely tuned to the second, the light had clockworks with weights that needed to be attended nearly every minute to ensure that the flash pattern was accurate. During the day, curtains were drawn over the lenses.

![]()

After the Sanibel lighthouse was completed, families started to arrive and by 1889, there were 21 houses, 40 families consisting of less than 100 people living in only 21 homes on Sanibel, that’s 2 families in most homes. These homesteaders included Anna and Sam Woodring (Woodring Point), The Nutt Family (Gray Gables) was on West Gulf Drive, The Rutland’s (The Rutland House is preserved in the Sanibel Historical Museum), and Capt. William Reed (First Post Office at Reeds Landing Tarpon Bay). Homestead rules mandated that you must stay 5 years and farm the land and never raise arms against the United States. Because many men had been confederates during the Civil War, this resulted in many homesteads registered in the wife’s name.

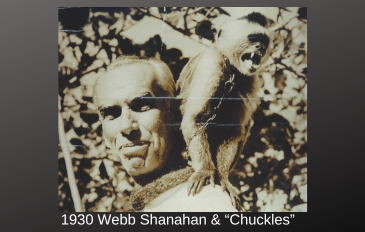

In 1890, Henry Shanahan became the assistant lighthouse keeper and when Dudley left in 1892, Shanahan wanted the position but his inability to read or write prevented his promotion until he threatened to quit. One can only assume there was not fierce competition for this position and Shanahan’s illiteracy was overlooked and he was promoted. When his wife passed away, Shanahan was left with 7 children and he married Irene Rutland, a Sanibel widow who had 5 children and together they had another son. During this time, Shanahan’s 13 children helped with the lighthouse responsibilities. Henry Shanahan remained the lighthouse keeper until he passed away in 1913. Over the years 2 sons and one stepson of Shanahan’s assisted in keeping the lighthouse running until it was automated.

![]()

In 1923, both lighthouse keeper houses were upgraded with indoor plumbing during a complete remodel. The original Fresnel lens was also replaced with a fixed third order lens. There are three types of lights used in lighthouses: flashing, fixed, or both combined to produce the unique pattern. This new lens produced the burst of light flash as it revolved by using bulls-eye panels which refract and deflect light vertically and horizontally while the lens revolved. Automation was used to turn the light on at night using a photocell on the southeast side of the top rail to detect the lack of sunlight. With the new level of technology came more time maintaining the advanced equipment employed to keep the lighthouse working flawlessly.

Sanibel’s lighthouse played a role in World War II during which time the US Coast Guard commandeered the light station in 1939. Growing fears of German U-Boats and invasions were grave possibilities. In 1942 a Submarine spotting tower was erected on the lighthouse grounds and a third building was constructed to house the Coast Guard. Beaches were patrolled looking for any landfall by the enemy. These fears were not irrational. A German submarine sank off the coast of Gasparilla Island indicating that U-boats were patrolling the Gulf of Mexico. During this same time period, Bowman’s Beach on Sanibel Island was being used for bombing practice by B-17s flying out of Buckingham Field for the Army Airforce.

![]()

After WWII the Fish and Wildlife Service was allowed use of the buildings at the Coast Guard light station at which time it became the headquarters of the Sanibel National Wildlife Refuge (J. N. Ding Darling Refuge). Charles LeBuff a refuge employee served both the refuge and maintained the the acetylene gas supply needed to maintain the light. He used his Army Jeep, ropes and pulleys to hoist the three massive tanks of highly flammable gas into place twice a year. To learn more about LeBuff’s incredible Sanibel history be sure read his autobiography “Sanybel Light”. LeBuff is also featured on Pfeifer Realty Group’s documentary: Sanibel Before the Causeway. One of LeBuff’s least favorite chores was cleaning out the giant cisterns that collected rain water. This had to be done by hand and as one can imagine the critters both dead and alive were unwelcome guests. Due to asbestos in the roof, the water was deemed undrinkable and bottled water was the only alternative.

![]()

It wasn’t until 1962 that electricity came to the Sanibel Lighthouse after the construction of the causeway and once again the lens needed to be changed to dovetail with the power source. The new 500 millimeter drum lens from a lightship was installed. Lightships were used in waters that were too deep to construct a lighthouse. This drum lens lasted until the early 80s when it was removed and displayed at the Sanibel Historical Village. The new lens was a 150 mm plastic lens which remains in use today.

In 2022, Hurricane Ian destroyed both lighthouse keeper’s quarters sweeping them out to sea and breaks one of the 4 iron legs of the Historical Sanibel Lighthouse. As a symbol of resilience and strength, the lighthouse leg was repaired and was relit 5 months after Ian made landfall. A large crowd gathered to celebrate the return of our beloved Point Ybel Light, a symbol of strength, resilience and resolve.

Our Sanibel Lighthouse is a beacon to all of us and represents the love we have for this Island and all those that came before us to create the paradise we love.

Sanibel Island Lighthouse Historical Timeline:

1856 – First Request to Build a Lighthouse on Sanibel

1877 – Second Request for Funds to Build the Lighthouse

1883 – Funds Approved to Build the Lighthouse $50,000

1884 - August 20th: Lighthouse is Lit For the First Time

1884 – 1892: Dudley Richardson, Keeper

1892 – 1913: Henry Shanahan, Keeper Assisted by his son Eugene Shanahan

1913 – 1923: Charles Williams, Keeper Assisted by: Clarence Rutland, Henry Shanahan’s stepson

1923 - Plumbing was Added to the Lighthouse Keeper Quarters

1923 - Fuel Switched from Kerosine to Acetylene Gas & A New Fixed Third Order Lens Installed

1924 – 1926: Eugene Shanahan, Keeper (Henry Shanahan’s son)

1926 – 1932: William Demere, Keeper

1932 – 1935: Roscoe McLane, Keeper

1935 – 1946: Richard J. Palmer

1939 - US Coastguard Takes over the Lighthouse During WWII

1942 - A German Submarine Spotting Tower is Built

1949 - US Fish & Wildlife take over the Lighthouse Service

1946 – 1949: William Robert England, Keeper Assisted by Webb Shanahan (Henry’s son)

1949 - Lighthouse was Automated no Longer Requiring Keepers

1950 – Cisterns Constructed to Capture Rain Water

1958 – 1979: Charles LeBuff, Ding Darling Employee Lighthouse Resident

1960 - Hurricane Donna Destroys the U-boat Spotting Tower

1962 - Causeway Completion brings Electricity to the Lighthouse

1962 – Lens Replaced with 55 mm Drum Lens from a Lightship

1974 - Lighthouse is placed on the National Registry of Historic Places.

1980s – Drum Lens Replaced by 190 mm Plastic Lens

2022 - Hurricane Ian Washes The Keeper’s Quarters Out to Sea on Sept. 28th

2023 - February 28th, Lighthouse Tower is Lit for the First Time 5 Months After Ian

Sanibel and Captiva Islands have a rich history, one that we can share with you visually, thanks to the efforts of David E. Carter for preserving valuable photographs and post cards as part of the Pfeifer Vintage Photo Collection as the Sanibel Public Library.

- History of Sanibel Homesteaders and Pioneer Families

- History of Shell Harbor Canals and Hugo Lindgren

- History of Casa Ybel Resort on Sanibel Island

- History of Sanibel's Island Inn

- Sanibel Before the Causeway

- Pfeifer Vintage Photo Collection

- "Sandbars to Sanibel" Filming on Location

- Post Cards and Photos from Sanibel The Sequel

- Post Cards and Pictures from Sanibel

- Sanibel Historical Village and Museum